Post by PaulsLaugh on Jun 5, 2022 5:32:16 GMT

www.msn.com/en-us/lifestyle/mind-and-soul/what-life-was-really-like-during-the-middle-ages/ar-AAY0c6V?ocid=msedgntp&cvid=9dc0e1c1801d4c7eb9fc8501399f85c9

Let's start with a little bit of a disclaimer: The term "Middle Ages" covers a lot of ground, starting with a millennium's worth of centuries. History says it's generally considered to be the period between the fall of the Roman Empire in 476, all the way into the 14th century and the Renaissance, and that's a long time by any standards. A lot happened in 1,000 years, give or take, and life experiences were incredibly different for people from all walks of life.

That said, defining what life was like is a little difficult -- and no, it wasn't the same for everyone. But there are some massive things that impacted people from the highest of the high to the lowest of the low, and that's stuff like the rise of organized religions like Christianity and Islam and the widespread death that came with the plague. Fun times? Not exactly.

Let's put some things in perspective, starting with the fact that it wasn't until the end of the era that Europe finally saw the development of 15 cities that had a population that topped just 50,000 people. (For comparison, Governing says that Union City, New Jersey has 54,138 people per square mile, and a whole city of that size looks like Galveston, Texas or La Crosse, Wisconsin.) Rural life was the norm, city life was growing, and everyday life? It looked a lot different than it does today.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Health, somewhere around 40 million Americans go through daily life while carrying the burden of an anxiety disorder. That's actually nothing new, and according to Hunter College professor of psychology and neuroscience Tracey A. Dennis-Tiwary, Ph.D. (via LitHub), those 40 million people can thank the Catholic Church for making anxiety a thing in the Middle Ages.

The word predates the Middle Ages, but it meant the sensation of being suffocated. Then the Church came along and decided it was something else: the soul's panicked, desperate desire for redemption through God.

More people were going to church services and were told they needed to make sure they prayed, said their penances, and gave confession, lest they end up in the clutches of eternity's torture demons. Saint Augustine summed up the whole thing like this: "God can relieve your troubles only if you in your anxiety cling to Him."

Michel Bourin, a professor at the University of Nantes, added (via the Archives of Depression and Anxiety) that there were other things at work here, too. Daily life in the Middle Ages was filled with prophetic visions about the end of the world, and other, more immediate threats. Death was agonizing and messy, and it lurked around every corner, along with accidents that could take away a family's livelihood in a heartbeat. In short, those living in the Middle Ages were finding out just how many things there were to worry about.

It's an oft-repeated bit of wisdom that people should get around eight hours of sleep, but according to the BBC, that wasn't the case during the Middle Ages. They spoke with historian and Virginia Tech professor Roger Ekirch, who has done some fascinating research into the sleep patterns of medieval Europeans.

Ekirch found scores of references to what's called biphasic sleep, or double sleeping. People would sleep for a few hours in the late evening, wake up for a few hours, and then go back to sleep. That bit of waking in the middle was incredibly important: Called "the watch," it was a time when people would tend the fires and candles -- their only source of light and heat -- check on the animals, or socialize. The devout had specific prayers that were said at this time, and it was also a time when families -- who often shared a bed out of necessity -- could just kind of hang out and talk.

Interestingly, modern experiments suggest there was something to this. In the 1990s, an experiment that started with the removal of external stimuli to get a group of people into a natural sleep rhythm found that the body defaulted to these two sleeps (via the BBC). Maybe ... bring that back?

Boston College economist and sociologist Juliet Schor is the author of "The Overworked American," which taps into one of her major areas of study: the work-life balance. She found that in the Middle Ages, things looked pretty different (via MIT).

In her research, she found that the idea of medieval peasants working from dawn to dusk wasn't exactly true: There were also three breaks for meals in there, along with rest periods. In many agricultural jobs, it depended on the season, too -- while planting and harvesting seasons were long and back-breaking, that wasn't a year-around thing. She also found that people were still working fewer hours per year than might be expected: Estimates suggest that in the 13th century, a peasant working 12 hours a day would accumulate about 1,620 working hours per year, while that number rose to between 3,150 and 3,650 working hours per year in the 1850s.

Why? Holidays. Schor pointed out that religion's impact on daily life meant that the Church mandated time off, including vacations during the big holidays like Christmas and Easter, along with the observations of saint's days throughout the year.

Let's take a few examples. In medieval France, workers were guaranteed 180 days off a year, while in Spain, they could expect not to work five months out of the year. In England, manor records from the 14th century say their workers only labored for 170 days out of the entire year.

Life in the Middle Ages wasn't all dirt and sweat. According to Rona Berg, a New York Times beauty columnist and author of several books on beauty, medieval people put more stock in beauty and cleanliness than they're often given credit for (via Enchanted Living).

Nobility tended to bathe regularly -- typically in water scented with oils and herbs -- and plucked their eyebrows and the front of the hairline to adhere to what beauty standards lauded for a long time. Perfumes were common, and once rosewater was brought back from the Middle East by soldiers and pilgrims, it became all the rage.

Powders were used to both give the illusion of pale skin and cover any skin blemishes that might be mistaken for the mark of the Devil -- a beauty routine that was arguably pretty practical at a time when no one wanted to be called a witch. Saffron and urine were used to lighten hair, pastes of milk and blood were used to whiten the skin, and no one said it wasn't disgusting.

There was even a 12th-century text called the Trotula that was pretty much a recipe book for teaching women the habits they should follow to look their best. Some make sense, like hiding a bundle of cloves, nutmeg, or other scents up in an elaborate hairstyle (via Medievalists). Others -- like instructions to remove freckles with a daily mix of powdered cuttlefish bones and frankincense -- were a bit stranger.

Concordia University professor Lucie Laumonier has compiled data sourced from medieval cities to figure out what the most common professions were (via Medievalists). She specifically looked at the French city of Montpellier, which had a pre-plague population of around 30,000 people. What did they do?

She found that about 25% of people living in the city and suburbs considered their occupation to be farmers, and in addition to working large-scale fields, they also raised livestock, worked in orchards, and tended vegetable beds.

Then there were the carpenters (6 percent), who worked on large-scale construction projects, built furniture, and chopped firewood. Butchers accounted for about 4 percent of Montpellier's population, and that meant there was roughly one butcher for every 300 people. There was about the same percentage of shoemakers, and about 2 percent of the city's people were working for the church.

Coming in at lower percentages but still in significant numbers were the tailors, notaries, barbers, retailers, and stonemasons, while women had their own professions. Per Medievalists, Laumonier says they often spent their days occupied with at-home work, like spinning, weaving, and needlework. Some women were employed as maids, while others ran their own businesses, including bakeries and pastry shops. Interestingly, she says that 20 percent of Montpellier's apprenticeship contracts from between 1300 and 1400 were for women training to learn a trade. Other cities had much lower rates, indicating a diversity of attitudes toward women working.

It's no secret that carbs are life, and it was like that in the Middle Ages, too -- even more so. Bread was the basis of diets throughout the era, and it was so important that most areas had laws governing everything from the making of to the sale of bread. The idea was to guarantee everyone has some, and the recommendation was "a lot" -- according to Medievalists, it was advised that people had at least two pounds of bread every day.

At the heart of bread's widespread popularity is the connection with Christ and the Last Supper: If it was a good enough last meal for Him, it was good enough for everyone else. Interestingly, historian Debby Banham said that Christianity is also why white bread was almost ridiculously popular (via Medievalists). In spite of the fact that it was much more difficult to make, it was long thought to be the best of the best, starting with the Christian conversion of three seventh-century kings. Those missionaries insisted on wheat-based white bread for the Eucharist, and white bread became wildly popular.

It was, however, expensive, and most of the working classes ate darker, whole-grain bread instead. The Middle Ages was a bread lover's paradise: Not only did Europeans bake bread from anything from rye and spelt to oats, rice, acorns, and peas, but a 10th-century text from Baghdad talks about a shocking number of light, thin, fermented, pan-sized, and seed-filled breads.

Life is about more than just what people did, it's about what surrounded them, too -- and in the Middle Ages, life in the city was defined by the bells.

According to medieval historian Daniele Cybulskie (via Medievalists), the soundtrack of the Middle Ages was punctuated by the ringing of bells -- particularly in the cities and even smaller towns where there were religious buildings or monasteries. Ringing bells called the devout to worship, and they also rang to signal other events, like deaths.

As the Middle Ages rolled on, more and more bells were built. Medievalists says that belfries -- towers with bells at the top -- were seen as signs of a city's success, and dozens of surviving bell towers have been earmarked as World Heritage sites.

The bells are called carillon, and given that the name comes from the French word for quarter, it's safe to say that most of them were rung every 15 minutes. And they made a lot of noise: The largest carillon in the Flanders region of Europe has a whopping 78 bells, so imagine that tolling across the city. It was loud, sure, but there was a bonus: Life in a medieval city was always on schedule, and everyone could use the bells as their own ever-present timepieces.

It's often repeated that people in the Middle Ages didn't have the life expectancy that people have come to expect of the 21st century, but that's not to say that everyone died suddenly and in the prime of their life. So, what kind of support was provided to the elderly?

Lucie Laumonier, a professor at Concordia University, says (via Medievalists) that elderly family members were typically cared for -- or provided for -- by their relatives. For those who had no family and no support system, evidence from historical records suggests it was understood that those in the community would offer support, friendship, and comfort to their elderly neighbors.

There were a few different social structures in place to make sure the elderly were fed and cared for when they could no longer work, with part of the responsibility falling on the wealthy. Many would provide pensions for their own servants so they could live comfortably once they aged out of work, and donated heavily to provide for elderly individuals in need. Monasteries would typically devote alms to the support of not just the elderly, but also widows, orphans, and the disabled.

If a person had been a part of a guild or fraternal society, these organizations also had resources devoted to elder care. It was widely considered just the good thing to do, with many of the elderly cared for and housed in hospitals associated with religious communities.

Perfectionism is a drive so deep-seated in many people that it's not always recognizable as something that's potentially harmful. According to the BBC, the need to be perfect -- and the mental and emotional struggles that happen when we inevitably fall short -- are linked to a slew of health problems. Interestingly, people in the Middle Ages were living with the same burden.

That's according to Irina Dumitrescu, a medieval scholar at Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universitat Bonn. She says that a study of medieval literature reveals just how obsessed the era was not only with perfection but also with reminding people that they were deeply fallible (via the CBC).

She cited works including the autobiography of Margery Kempe, "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight," and the works of Geoffrey Chaucer -- particularly the story of the Wife of Bath. Each illustrated the perfect ideal: The purity of the lives of saints, the ideals of chivalry, and the perfection of virginity, respectively. Dumitrescu found it was a recurring theme: Medieval literature told people how perfect they should be in the spiritual and physical realms, and then added more thoughts on why they weren't going to achieve that perfection. She explained it in this context: "Margery suffered from what often feels like a modern scourge: Not just a desire to be perfect in the eyes of God, but a nagging, frustrating perfectionism she couldn't shake."

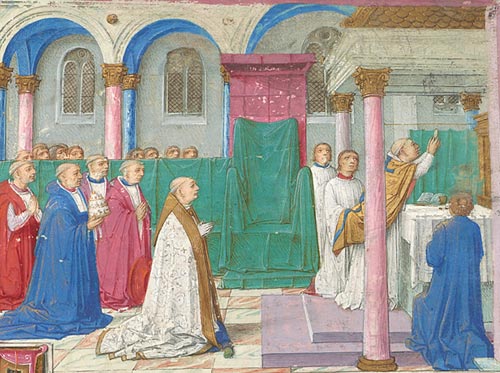

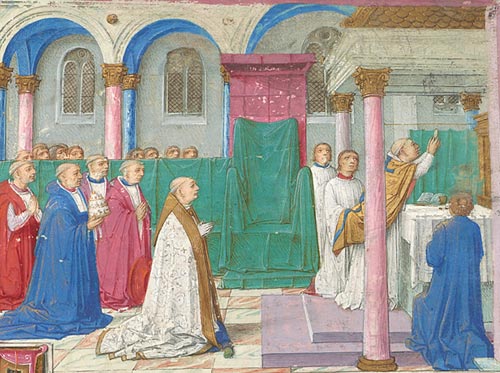

Religion helped shape the daily life of countless people throughout the Middle Ages, but it was also pretty complicated.

According to World History, Christianity did a slow crawl across the world over the course of centuries, dividing people into new Christians and old pagans. As the Catholic Church grew, old practices -- like fortune-telling, offering gifts to earth and water spirits, or saying spells and incantations while planting crops -- were deemed heretical in some cases and were allowed to continue in others, particularly where people also embraced Christian rites like prayer and confession.

On an everyday level, even devout Christians in the Middle Ages didn't have much to do with things like saying Mass: It was recited in Latin, with the priest facing away from his congregation. Instead, it was the baptismal font that presented the everyday person with a connection to their new faith, with the belief that it was the source of a person's purely spiritual life.

Christianity evolved a lot over the course of 1,000 years: The so-called Cult of Mary became incredibly important, the church took an increasingly harsher stance toward heretical groups like the Cathars, and the Crusades formed the backdrop of life for hundreds of years. Through it all, many ordinary people continued to cling to the same folk beliefs they had for generations. The clergy had a habit of looking in the other direction when it came to many old pagan rituals, making the Middle Ages a kind of mish-mash of old and new.

There's a nasty rumor about medieval teeth that's repeated a lot, and it's basically that they were, well, nasty. That's not the case at all, says historian Tim O'Neill (via Slate). Not only were white teeth and pleasant breath considered desirable, but people also tended to make dental care a part of their daily routine.

Tooth decay was actually fairly rare, for a few reasons -- starting with the lack of added sugars in the typical diet. Also diet-related was the impact that coarsely-ground bread had: This staple of medieval diets meant that teeth wore differently than they do today, and were typically smoother. That meant there were fewer places for bacteria to get stuck, and when they cleaned their teeth -- which they did often, usually with linen cloths -- they would remove particles before they turned into problems.

Historian Daniele Cybulskie says that regularly using toothpaste was absolutely a common thing, too. She's found some medieval recipes for making homemade toothpaste (via Medievalists), and they don't all sound terrible. Some called for using powdered walnut shells and rinsing with warm wine, while others suggested a powder made of spices and herbs like cinnamon, wormwood, olives, date pits, and clove. Traveling? There were recommendations for taking toothpaste with you, in the form of balls of sage and salt that were baked and then chewed for some nice, clean teeth.

Were good boys and good girls making life in the Middle Ages better for people? Absolutely!

According to History Today, the world of pet ownership evolved throughout the era. While many dogs served their families as hunting or herding dogs or acted as protection, they were also cherished pets. Stories of the intelligence and loyalty of dogs were lauded as examples of the finest little souls around, and when people traveled -- and even when they attended church -- their faithful companions often went with them. Names of cherished dogs were documented in medieval texts, and Medievalists says historical records have preserved the memories of dogs with names like Jakke, Terri, and Furst, which translates to "Prince."

Cats had a slightly more complicated relationship with people, says Medievalists, stemming from the newly-added Christian belief that cats played with their prey like the Devil played with human souls. Still, the lives of medieval people were often made easier by the presence of vermin-controlling cats, with the names of some -- particularly those living in monasteries and abbeys -- recorded in historical documents. A poem describes the cat of a ninth-century monk as being named Pangur Ban, while Mite kept Beaulieu Abbey mouse-free in the 13th century, and Belaud patrolled Joachim du Bellay a few centuries later.

It's a given that rural living is going to come with gardens, but according to research done by historian Caroline Goodson (via the University of Cambridge), gardens in the middle of medieval cities weren't uncommon. Open areas between and behind houses were often used for everything from vegetable gardens to vineyards, and perhaps most surprisingly, mentions of urban gardens not only started showing up in historical records dating back to the sixth century, but they also became more common as the Middle Ages went on.

Some cities were even overhauled to incorporate more gardens inside city walls. Lucca, for example, went from a city where houses were packed shoulder-to-shoulder in the Roman era to a medieval city with enough green space that city-dwellers could have their own gardens.

Concordia University professor Lucie Laumonier says that her research has found that medieval cities were much greener than modern-day cities, and so-called urban peasants often had their own spaces that would provide valuable herbs and vegetables to families (via Medievalists). These green spaces started to decrease as cities became more and more crowded, but after the population dropped during plague pandemics, they were often reclaimed by those who survived and turned back into gardens.

Gardens weren't all about the food, either: Medieval physicians recommended everyone literally take time to smell the roses, citing walks in nature as having the ability to lift mood, as well as improve mental and physical health.

Respect for the dead has always been one of the defining aspects of human culture, and different cultures showed respect in a variety of ways. That's true of the Middle Ages, and archaeologists have discovered some fascinating things about what saying that final farewell was like for those living -- and dying -- in medieval times.

According to National Geographic, an investigation into burial positions turned up the occasional face-down burial. Between about 950 and 1300, there weren't a ton of these burials, but given their central location in church cemeteries and the finery they were buried with, it's believed some would opt to be buried face-down as a way of showing humility and penance.

Bodies were typically washed, wrapped, and kept in the home for a few days, as the community said their goodbyes. Services would be held at the church, and deaths would typically be recorded by the Office of the Dead so names could be recited long after the person had passed. According to research done by the University of Guelph, it was incredibly important for people -- particularly the clergy -- to remember and pray for the dead, to help them on their way to heaven.

Yvonne Inall, a research assistant from the University of Hull, adds this not-so-fun fact (via The Conversation): Coffins were communal. Bodies were often buried in shrouds because families would have to give the coffin back to the church.

That said, defining what life was like is a little difficult -- and no, it wasn't the same for everyone. But there are some massive things that impacted people from the highest of the high to the lowest of the low, and that's stuff like the rise of organized religions like Christianity and Islam and the widespread death that came with the plague. Fun times? Not exactly.

Let's put some things in perspective, starting with the fact that it wasn't until the end of the era that Europe finally saw the development of 15 cities that had a population that topped just 50,000 people. (For comparison, Governing says that Union City, New Jersey has 54,138 people per square mile, and a whole city of that size looks like Galveston, Texas or La Crosse, Wisconsin.) Rural life was the norm, city life was growing, and everyday life? It looked a lot different than it does today.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Health, somewhere around 40 million Americans go through daily life while carrying the burden of an anxiety disorder. That's actually nothing new, and according to Hunter College professor of psychology and neuroscience Tracey A. Dennis-Tiwary, Ph.D. (via LitHub), those 40 million people can thank the Catholic Church for making anxiety a thing in the Middle Ages.

The word predates the Middle Ages, but it meant the sensation of being suffocated. Then the Church came along and decided it was something else: the soul's panicked, desperate desire for redemption through God.

More people were going to church services and were told they needed to make sure they prayed, said their penances, and gave confession, lest they end up in the clutches of eternity's torture demons. Saint Augustine summed up the whole thing like this: "God can relieve your troubles only if you in your anxiety cling to Him."

Michel Bourin, a professor at the University of Nantes, added (via the Archives of Depression and Anxiety) that there were other things at work here, too. Daily life in the Middle Ages was filled with prophetic visions about the end of the world, and other, more immediate threats. Death was agonizing and messy, and it lurked around every corner, along with accidents that could take away a family's livelihood in a heartbeat. In short, those living in the Middle Ages were finding out just how many things there were to worry about.

It's an oft-repeated bit of wisdom that people should get around eight hours of sleep, but according to the BBC, that wasn't the case during the Middle Ages. They spoke with historian and Virginia Tech professor Roger Ekirch, who has done some fascinating research into the sleep patterns of medieval Europeans.

Ekirch found scores of references to what's called biphasic sleep, or double sleeping. People would sleep for a few hours in the late evening, wake up for a few hours, and then go back to sleep. That bit of waking in the middle was incredibly important: Called "the watch," it was a time when people would tend the fires and candles -- their only source of light and heat -- check on the animals, or socialize. The devout had specific prayers that were said at this time, and it was also a time when families -- who often shared a bed out of necessity -- could just kind of hang out and talk.

Interestingly, modern experiments suggest there was something to this. In the 1990s, an experiment that started with the removal of external stimuli to get a group of people into a natural sleep rhythm found that the body defaulted to these two sleeps (via the BBC). Maybe ... bring that back?

Boston College economist and sociologist Juliet Schor is the author of "The Overworked American," which taps into one of her major areas of study: the work-life balance. She found that in the Middle Ages, things looked pretty different (via MIT).

In her research, she found that the idea of medieval peasants working from dawn to dusk wasn't exactly true: There were also three breaks for meals in there, along with rest periods. In many agricultural jobs, it depended on the season, too -- while planting and harvesting seasons were long and back-breaking, that wasn't a year-around thing. She also found that people were still working fewer hours per year than might be expected: Estimates suggest that in the 13th century, a peasant working 12 hours a day would accumulate about 1,620 working hours per year, while that number rose to between 3,150 and 3,650 working hours per year in the 1850s.

Why? Holidays. Schor pointed out that religion's impact on daily life meant that the Church mandated time off, including vacations during the big holidays like Christmas and Easter, along with the observations of saint's days throughout the year.

Let's take a few examples. In medieval France, workers were guaranteed 180 days off a year, while in Spain, they could expect not to work five months out of the year. In England, manor records from the 14th century say their workers only labored for 170 days out of the entire year.

Life in the Middle Ages wasn't all dirt and sweat. According to Rona Berg, a New York Times beauty columnist and author of several books on beauty, medieval people put more stock in beauty and cleanliness than they're often given credit for (via Enchanted Living).

Nobility tended to bathe regularly -- typically in water scented with oils and herbs -- and plucked their eyebrows and the front of the hairline to adhere to what beauty standards lauded for a long time. Perfumes were common, and once rosewater was brought back from the Middle East by soldiers and pilgrims, it became all the rage.

Powders were used to both give the illusion of pale skin and cover any skin blemishes that might be mistaken for the mark of the Devil -- a beauty routine that was arguably pretty practical at a time when no one wanted to be called a witch. Saffron and urine were used to lighten hair, pastes of milk and blood were used to whiten the skin, and no one said it wasn't disgusting.

There was even a 12th-century text called the Trotula that was pretty much a recipe book for teaching women the habits they should follow to look their best. Some make sense, like hiding a bundle of cloves, nutmeg, or other scents up in an elaborate hairstyle (via Medievalists). Others -- like instructions to remove freckles with a daily mix of powdered cuttlefish bones and frankincense -- were a bit stranger.

Concordia University professor Lucie Laumonier has compiled data sourced from medieval cities to figure out what the most common professions were (via Medievalists). She specifically looked at the French city of Montpellier, which had a pre-plague population of around 30,000 people. What did they do?

She found that about 25% of people living in the city and suburbs considered their occupation to be farmers, and in addition to working large-scale fields, they also raised livestock, worked in orchards, and tended vegetable beds.

Then there were the carpenters (6 percent), who worked on large-scale construction projects, built furniture, and chopped firewood. Butchers accounted for about 4 percent of Montpellier's population, and that meant there was roughly one butcher for every 300 people. There was about the same percentage of shoemakers, and about 2 percent of the city's people were working for the church.

Coming in at lower percentages but still in significant numbers were the tailors, notaries, barbers, retailers, and stonemasons, while women had their own professions. Per Medievalists, Laumonier says they often spent their days occupied with at-home work, like spinning, weaving, and needlework. Some women were employed as maids, while others ran their own businesses, including bakeries and pastry shops. Interestingly, she says that 20 percent of Montpellier's apprenticeship contracts from between 1300 and 1400 were for women training to learn a trade. Other cities had much lower rates, indicating a diversity of attitudes toward women working.

It's no secret that carbs are life, and it was like that in the Middle Ages, too -- even more so. Bread was the basis of diets throughout the era, and it was so important that most areas had laws governing everything from the making of to the sale of bread. The idea was to guarantee everyone has some, and the recommendation was "a lot" -- according to Medievalists, it was advised that people had at least two pounds of bread every day.

At the heart of bread's widespread popularity is the connection with Christ and the Last Supper: If it was a good enough last meal for Him, it was good enough for everyone else. Interestingly, historian Debby Banham said that Christianity is also why white bread was almost ridiculously popular (via Medievalists). In spite of the fact that it was much more difficult to make, it was long thought to be the best of the best, starting with the Christian conversion of three seventh-century kings. Those missionaries insisted on wheat-based white bread for the Eucharist, and white bread became wildly popular.

It was, however, expensive, and most of the working classes ate darker, whole-grain bread instead. The Middle Ages was a bread lover's paradise: Not only did Europeans bake bread from anything from rye and spelt to oats, rice, acorns, and peas, but a 10th-century text from Baghdad talks about a shocking number of light, thin, fermented, pan-sized, and seed-filled breads.

Life is about more than just what people did, it's about what surrounded them, too -- and in the Middle Ages, life in the city was defined by the bells.

According to medieval historian Daniele Cybulskie (via Medievalists), the soundtrack of the Middle Ages was punctuated by the ringing of bells -- particularly in the cities and even smaller towns where there were religious buildings or monasteries. Ringing bells called the devout to worship, and they also rang to signal other events, like deaths.

As the Middle Ages rolled on, more and more bells were built. Medievalists says that belfries -- towers with bells at the top -- were seen as signs of a city's success, and dozens of surviving bell towers have been earmarked as World Heritage sites.

The bells are called carillon, and given that the name comes from the French word for quarter, it's safe to say that most of them were rung every 15 minutes. And they made a lot of noise: The largest carillon in the Flanders region of Europe has a whopping 78 bells, so imagine that tolling across the city. It was loud, sure, but there was a bonus: Life in a medieval city was always on schedule, and everyone could use the bells as their own ever-present timepieces.

It's often repeated that people in the Middle Ages didn't have the life expectancy that people have come to expect of the 21st century, but that's not to say that everyone died suddenly and in the prime of their life. So, what kind of support was provided to the elderly?

Lucie Laumonier, a professor at Concordia University, says (via Medievalists) that elderly family members were typically cared for -- or provided for -- by their relatives. For those who had no family and no support system, evidence from historical records suggests it was understood that those in the community would offer support, friendship, and comfort to their elderly neighbors.

There were a few different social structures in place to make sure the elderly were fed and cared for when they could no longer work, with part of the responsibility falling on the wealthy. Many would provide pensions for their own servants so they could live comfortably once they aged out of work, and donated heavily to provide for elderly individuals in need. Monasteries would typically devote alms to the support of not just the elderly, but also widows, orphans, and the disabled.

If a person had been a part of a guild or fraternal society, these organizations also had resources devoted to elder care. It was widely considered just the good thing to do, with many of the elderly cared for and housed in hospitals associated with religious communities.

Perfectionism is a drive so deep-seated in many people that it's not always recognizable as something that's potentially harmful. According to the BBC, the need to be perfect -- and the mental and emotional struggles that happen when we inevitably fall short -- are linked to a slew of health problems. Interestingly, people in the Middle Ages were living with the same burden.

That's according to Irina Dumitrescu, a medieval scholar at Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universitat Bonn. She says that a study of medieval literature reveals just how obsessed the era was not only with perfection but also with reminding people that they were deeply fallible (via the CBC).

She cited works including the autobiography of Margery Kempe, "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight," and the works of Geoffrey Chaucer -- particularly the story of the Wife of Bath. Each illustrated the perfect ideal: The purity of the lives of saints, the ideals of chivalry, and the perfection of virginity, respectively. Dumitrescu found it was a recurring theme: Medieval literature told people how perfect they should be in the spiritual and physical realms, and then added more thoughts on why they weren't going to achieve that perfection. She explained it in this context: "Margery suffered from what often feels like a modern scourge: Not just a desire to be perfect in the eyes of God, but a nagging, frustrating perfectionism she couldn't shake."

Religion helped shape the daily life of countless people throughout the Middle Ages, but it was also pretty complicated.

According to World History, Christianity did a slow crawl across the world over the course of centuries, dividing people into new Christians and old pagans. As the Catholic Church grew, old practices -- like fortune-telling, offering gifts to earth and water spirits, or saying spells and incantations while planting crops -- were deemed heretical in some cases and were allowed to continue in others, particularly where people also embraced Christian rites like prayer and confession.

On an everyday level, even devout Christians in the Middle Ages didn't have much to do with things like saying Mass: It was recited in Latin, with the priest facing away from his congregation. Instead, it was the baptismal font that presented the everyday person with a connection to their new faith, with the belief that it was the source of a person's purely spiritual life.

Christianity evolved a lot over the course of 1,000 years: The so-called Cult of Mary became incredibly important, the church took an increasingly harsher stance toward heretical groups like the Cathars, and the Crusades formed the backdrop of life for hundreds of years. Through it all, many ordinary people continued to cling to the same folk beliefs they had for generations. The clergy had a habit of looking in the other direction when it came to many old pagan rituals, making the Middle Ages a kind of mish-mash of old and new.

There's a nasty rumor about medieval teeth that's repeated a lot, and it's basically that they were, well, nasty. That's not the case at all, says historian Tim O'Neill (via Slate). Not only were white teeth and pleasant breath considered desirable, but people also tended to make dental care a part of their daily routine.

Tooth decay was actually fairly rare, for a few reasons -- starting with the lack of added sugars in the typical diet. Also diet-related was the impact that coarsely-ground bread had: This staple of medieval diets meant that teeth wore differently than they do today, and were typically smoother. That meant there were fewer places for bacteria to get stuck, and when they cleaned their teeth -- which they did often, usually with linen cloths -- they would remove particles before they turned into problems.

Historian Daniele Cybulskie says that regularly using toothpaste was absolutely a common thing, too. She's found some medieval recipes for making homemade toothpaste (via Medievalists), and they don't all sound terrible. Some called for using powdered walnut shells and rinsing with warm wine, while others suggested a powder made of spices and herbs like cinnamon, wormwood, olives, date pits, and clove. Traveling? There were recommendations for taking toothpaste with you, in the form of balls of sage and salt that were baked and then chewed for some nice, clean teeth.

Were good boys and good girls making life in the Middle Ages better for people? Absolutely!

According to History Today, the world of pet ownership evolved throughout the era. While many dogs served their families as hunting or herding dogs or acted as protection, they were also cherished pets. Stories of the intelligence and loyalty of dogs were lauded as examples of the finest little souls around, and when people traveled -- and even when they attended church -- their faithful companions often went with them. Names of cherished dogs were documented in medieval texts, and Medievalists says historical records have preserved the memories of dogs with names like Jakke, Terri, and Furst, which translates to "Prince."

Cats had a slightly more complicated relationship with people, says Medievalists, stemming from the newly-added Christian belief that cats played with their prey like the Devil played with human souls. Still, the lives of medieval people were often made easier by the presence of vermin-controlling cats, with the names of some -- particularly those living in monasteries and abbeys -- recorded in historical documents. A poem describes the cat of a ninth-century monk as being named Pangur Ban, while Mite kept Beaulieu Abbey mouse-free in the 13th century, and Belaud patrolled Joachim du Bellay a few centuries later.

It's a given that rural living is going to come with gardens, but according to research done by historian Caroline Goodson (via the University of Cambridge), gardens in the middle of medieval cities weren't uncommon. Open areas between and behind houses were often used for everything from vegetable gardens to vineyards, and perhaps most surprisingly, mentions of urban gardens not only started showing up in historical records dating back to the sixth century, but they also became more common as the Middle Ages went on.

Some cities were even overhauled to incorporate more gardens inside city walls. Lucca, for example, went from a city where houses were packed shoulder-to-shoulder in the Roman era to a medieval city with enough green space that city-dwellers could have their own gardens.

Concordia University professor Lucie Laumonier says that her research has found that medieval cities were much greener than modern-day cities, and so-called urban peasants often had their own spaces that would provide valuable herbs and vegetables to families (via Medievalists). These green spaces started to decrease as cities became more and more crowded, but after the population dropped during plague pandemics, they were often reclaimed by those who survived and turned back into gardens.

Gardens weren't all about the food, either: Medieval physicians recommended everyone literally take time to smell the roses, citing walks in nature as having the ability to lift mood, as well as improve mental and physical health.

Respect for the dead has always been one of the defining aspects of human culture, and different cultures showed respect in a variety of ways. That's true of the Middle Ages, and archaeologists have discovered some fascinating things about what saying that final farewell was like for those living -- and dying -- in medieval times.

According to National Geographic, an investigation into burial positions turned up the occasional face-down burial. Between about 950 and 1300, there weren't a ton of these burials, but given their central location in church cemeteries and the finery they were buried with, it's believed some would opt to be buried face-down as a way of showing humility and penance.

Bodies were typically washed, wrapped, and kept in the home for a few days, as the community said their goodbyes. Services would be held at the church, and deaths would typically be recorded by the Office of the Dead so names could be recited long after the person had passed. According to research done by the University of Guelph, it was incredibly important for people -- particularly the clergy -- to remember and pray for the dead, to help them on their way to heaven.

Yvonne Inall, a research assistant from the University of Hull, adds this not-so-fun fact (via The Conversation): Coffins were communal. Bodies were often buried in shrouds because families would have to give the coffin back to the church.