'Strangers On A Train' & Patricia Highsmith Film Adaptations

May 5, 2024 1:12:58 GMT

Catman, politicidal1, and 10 more like this

Post by petrolino on May 5, 2024 1:12:58 GMT

Patricia Highsmith (born January 19, 1921 in Fort Worth, Texas, U.S.)

I've read in the past that novelists Raymond Chandler, Czenzi Ormonde and Whitfield Cook were all involved in the creative process behind bringing Patricia Highsmith's debut novel 'Strangers On A Train' (1950) to the screen, with Ben Hecht having passed on the opportunity. There were other writers involved too, with director Alfred Hitchcock bringing it all together to shoot 'Strangers On A Train' (1951), the warped story of tennis player Guy Haines (Farley Granger) and his unsettling encounter with manipulative, smooth-talking sociopath Bruno Antony (Robert Walker). At the core of this twisted tale's dark heart is a discussion around how to commit the perfect murder.

'The theme of doubles is "the key element in the film's structure," and Alfred Hitchcock starts right off in his title sequence making this point: there are two taxicabs, two redcaps, two pairs of feet, two sets of train rails that cross twice. Once on the train, Bruno orders a pair of double drinks — "The only kind of doubles I play", he says charmingly. In Hitchcock's cameo he carries a double bass.

There are two respectable and influential fathers, two women with eyeglasses, and two women at a party who delight in thinking up ways of committing the perfect crime. There are two sets of two detectives in two cities, two little boys at the two trips to the fairground, two old men at the carousel, two boyfriends accompanying the woman about to be murdered, and two Hitchcocks in the film.

Hitchcock carries the theme into his editing, crosscutting between Guy and Bruno with words and gestures: one asks the time and the other, miles away, looks at his watch; one says in anger "I could strangle her!" and the other, far distant, makes a choking gesture.

This doubling has some precedent in the novel, but more of it was deliberately added by Hitchcock, "dictated in rapid and inspired profusion to Czenzi Ormonde and Barbara Keon during the last days of script preparation." It undergirds the whole film because it finally serves to associate the world of light, order, and vitality with the world of darkness, chaos, lunacy and death."

Guy and Bruno are in some ways doubles, but in many more ways, they are opposites. The two sets of feet in the title sequence match each other in motion and in cutting, but they immediately establish the contrast between the two men : the first shoes "showy, vulgar brown-and-white brogues; [the] second, plain, unadorned walking shoes." They also demonstrate Hitchcock's gift for deft visual storytelling: For most of the film, Bruno is the actor, Guy the reactor, and Hitchcock always shows Bruno's feet first, then Guy's. And since it is Guy's foot that taps Bruno's under the table, we know Bruno has not engineered the meeting.'

There are two respectable and influential fathers, two women with eyeglasses, and two women at a party who delight in thinking up ways of committing the perfect crime. There are two sets of two detectives in two cities, two little boys at the two trips to the fairground, two old men at the carousel, two boyfriends accompanying the woman about to be murdered, and two Hitchcocks in the film.

Hitchcock carries the theme into his editing, crosscutting between Guy and Bruno with words and gestures: one asks the time and the other, miles away, looks at his watch; one says in anger "I could strangle her!" and the other, far distant, makes a choking gesture.

This doubling has some precedent in the novel, but more of it was deliberately added by Hitchcock, "dictated in rapid and inspired profusion to Czenzi Ormonde and Barbara Keon during the last days of script preparation." It undergirds the whole film because it finally serves to associate the world of light, order, and vitality with the world of darkness, chaos, lunacy and death."

Guy and Bruno are in some ways doubles, but in many more ways, they are opposites. The two sets of feet in the title sequence match each other in motion and in cutting, but they immediately establish the contrast between the two men : the first shoes "showy, vulgar brown-and-white brogues; [the] second, plain, unadorned walking shoes." They also demonstrate Hitchcock's gift for deft visual storytelling: For most of the film, Bruno is the actor, Guy the reactor, and Hitchcock always shows Bruno's feet first, then Guy's. And since it is Guy's foot that taps Bruno's under the table, we know Bruno has not engineered the meeting.'

- Wikipedia

'Strangers On A Train'

In 2021, 'Strangers On A Train' was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

- - -

Italian crime filmmakers were fascinated by Alfred Hitchcock's influential crime picture which received an unofficial partner in crime in the form of Maurizio Lucidi's giallo mystery 'The Designated Victim' (1971). Farley Granger lived and worked for many years in Italy.

Italian, French and German filmmakers picked up the baton from England's suspense master when it came to Patricia Highsmith's writing. This century, there's been a resurgence of her work in American cinema which is good to see, with international filmmakers coming from far and wide to help launch new adaptations.

'One Dyin' And A Buryin' - Roger Miller (born January 2, 1936 in Fort Worth, Texas, U.S.)

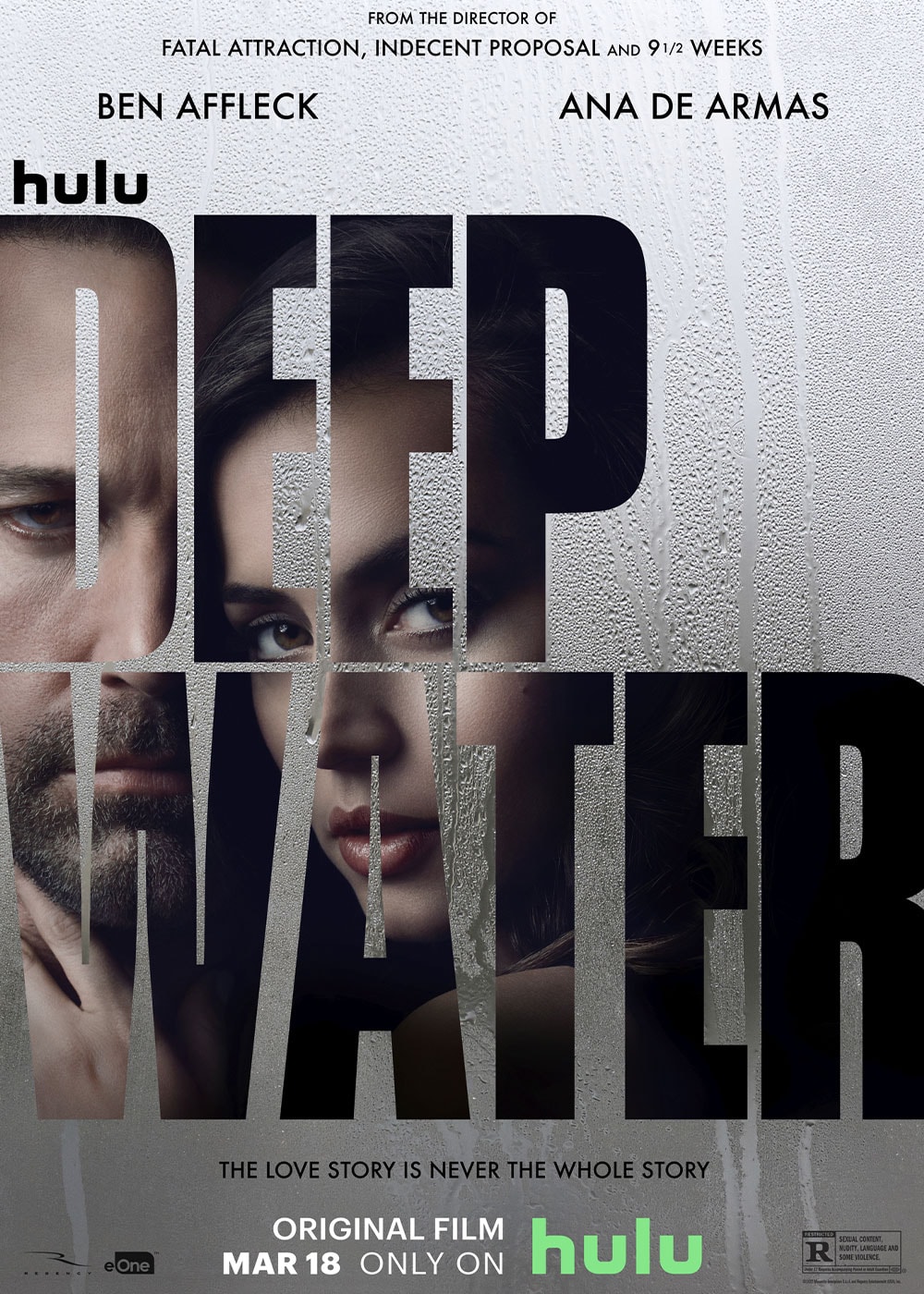

Here's my pick of the ten best adaptations among those I've seen, since first seeing 'Strangers On A Train' as a boy, which made an impression. Of those I've not seen, I'm especially keen to see Claude Autant-Lara's 'Enough Rope' (1963), Robert Sparr's 'Once You Kiss A Stranger' (1969) and Adrian Lyne's 'Deep Water' (2022).

'The Garden Of Souls' - Ornette Coleman (born March 9, 1930 in Fort Worth, Texas, U.S.)

-

01) 'Strangers On A Train' (1951) - Alfred Hitchcock / Based on the novel 'Strangers On A Train' (1950)

Kasey Rogers

02) 'Purple Noon' (1960, Plein soleil) - René Clément / Based on the novel 'The Talented Mr. Ripley' (1955)

~ Screenwriter Paul Gégauff was obsessive about Patricia Highsmith's novel which also informed Claude Chabrol's 'The Does' (1968, Les biches) which Gégauff co-wrote with Chabrol. Interestingly, Chabrol went on to direct 'The Cry Of The Owl' (1987, Le cri du hibou), an odd adaptation of Highsmith's novel 'The Cry Of The Owl' (1962).

Marie Laforêt & Alain Delon

03) 'The American Friend' (1977, Der amerikanische Freund) - Wim Wenders / Based on the novels 'Ripley Under Ground' (1970) & 'Ripley's Game' (1974)

Nicholas Ray

04) 'Tell Her I Love Her' (1977, Dites-lui que je l'aime) - Claude Miller / Based on the novel 'This Sweet Sickness' (1960)

Gérard Depardieu & Miou-Miou

05) 'Deep Water' (1981, Eaux profondes) - Michel Deville / Based on the novel 'Deep Water' (1957)

Isabelle Huppert, Jean-Louis Trintignant & Robin Renucci

06) 'Throw Momma From The Train' (1987) - Danny DeVito / Inspired by the novel 'Strangers On A Train' (1950)

Danny DeVito, Anne Ramsey & Billy Crystal

07) 'Ripley's Game' (2002, Il gioco di Ripley) - Liliana Cavani / Based on the novel 'Ripley's Game' (1974)

John Malkovich & Chiara Caselli

08) 'Ripley Under Ground' (2005) - Roger Spottiswoode / Based on the novel 'Ripley Under Ground' (1970)

Alan Cumming & Claire Forlani

09) 'The Two Faces Of January' (2014) - Hossein Amini / Based on the novel 'The Two Faces Of January' (1964)

Viggo Mortensen & Kirsten Dunst

10) 'Carol' (2015) - Todd Haynes / Based on the novel 'The Price Of Salt' (1952)

Rooney Mara

-

'Loving Highsmith' [Zeitgeist Films]